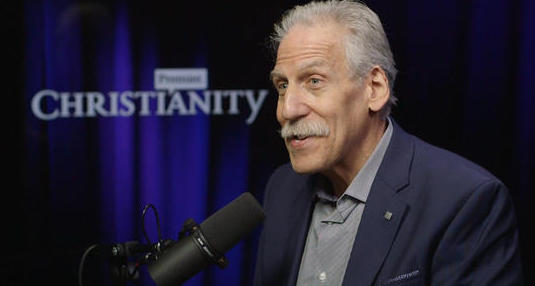

Michael Brown was a very judgy mood in his Jan. 19 WorldNetDaily column, complaining that “unashamed Christian” actor Alan Ritchson defended playing a “morally ambiguous” character and at one point did “a love scene in the shower with a topless woman.” He huffed:

I actually agree with him here. Christians should not be limited to acting in Christian roles alone. Obviously.

But the bigger question is more basic: Are there any lines that a Christian actor should not cross?

For example, could a committed Christian be a porn star? The answer is obviously not.

Brown’s judginess increased as the column continued:

What, then, does God’s Word have to say? What is the standard of heaven? (For the record, I did reach out to Ritchson through his agent listed online, but without success.)

Let’s make this simple.

What if this was you or me filming this scene? Or what if this was your spouse? How would you feel before God? And could you say to Jesus, “Let’s sit down together and watch this partially nude love scene I just filmed”?

I understand that actors act. But as one commenter on my X account noted, “I believe it was John Piper who helped with this by saying when a man in a film is shot by a gun, the director yells cut and the ‘dead’ man gets up having played the charade of being shot. When a person shows their nude body in a film, that is not a charade, but the real thing.”

[…]Husbands, how would you feel if your wife was the actress in the scene? If she were the one topless, hugging and kissing a topless man for millions to see? (Or even for no one to see.)

Wives, how would you feel if your husband was the one hugging and kissing the topless woman?

Brown then laughably denied he was being judgmental at all:

Again, I am not Alan Ritchson’s personal judge. It is God’s Word which judges us, and we both give account to Him.

More broadly, I’m not here to judge those who have struggled with porn or to condemn those who are involved with porn. Many of them are enslaved and want to be free. They need the Lord! And all of us, outside of God’s grace and the blood of Jesus, are worthy of damnation. Even on our best days, we still fall short. I live by mercy too.

At the same time, God calls us to holiness and purity, not out of legalism or rule-keeping but out of love and because we belong to Him.

It’s one thing to acknowledge God’s standards and say, “Lord, I need help! I keep falling short.” It’s another to lower His standards. We do that to our own harm.

That’s why many other Christian actors have refused to do sex scenes or nude scenes. For them, it meant a compromise of their faith.

Which, of course, is fine. But Brown is being completely judgmental of Ritchson while dishonestly pretending he’s not.

For his Jan. 22 column, Brown — just as he quibbled over the definition of the New Apostolic Reformation he considers himself a part of — debated the definition of “evangelical”:

When it comes to the term “evangelical,” it is not so much that it is a potentially ambiguous term (like “Christian”) as it is a misleading term, a term that has become cultural and political more than spiritual.

Explaining the history of the word “evangelical,” which first came into use in the 1500s as a synonym for “gospel,” Thomas Kidd notes that, “By 1950, the use of the word had changed dramatically, especially because of the founding of the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) in 1942. ‘Evangelical’ was coming to denote conversionist Protestants who were not fundamentalists.”

A major factor in this was that, “in 1949, Billy Graham rose to prominence, and by 1950 he had become the undisputed standard-bearer for what people saw as evangelical faith.”

Evangelicals, then, believed what Billy Graham believed. That was pretty simple.

But, Kidd explains, “in 1976. That year, Jimmy Carter, a self-described evangelical, won the presidency, and Newsweek declared 1976 the ‘year of the evangelical.’

Brown then complained that people with “their own biases” have associated “evangelical” leaders with political agendas, as if evangelical leaders themselves haven’t made that happen:

That’s why, for a decade or more, some evangelical leaders have suggested that we drop the term entirely, since to most Americans, it speaks of a cultural and political aspect of our faith more than the essence of our faith.

Recent studies suggest that the trend in that direction has deepened, with many conservative white voters (especially Trump supporters) self-identifying as evangelicals, even if some of them do not hold to traditional evangelical beliefs.

And so the term, which was first entirely spiritual in meaning, became a spiritual term with cultural and political associations, and now, perhaps, primarily a cultural and political term.

As noted in a January 8 article in the New York Times by Ruth Graham and Charles Homans, “Religion scholars, drawing on a growing body of data, suggest another explanation: Evangelicals are not exactly who they used to be. Being evangelical once suggested regular church attendance, a focus on salvation and conversion and strongly held views on specific issues such as abortion. Today, it is as often used to describe a cultural and political identity: one in which Christians are considered a persecuted minority, traditional institutions are viewed skeptically and Trump looms large.”

To be sure, some of the scholars cited might see things through the lens of their own biases, viewing many evangelical Trump supporters as white supremacists and/or insurrectionists.

But either way, there is no doubt that the term “evangelical” does not mean what it used to mean, especially to the general public.

Brown concluded by insisting that “committed Christians” understand what the word means, while suggesting that it has become somewhat toxic outside of those circles:

In house, among committed Christians who identify as evangelicals, or distinguishing between Catholic Christians and evangelical Christians, the term still speaks of those who hold to a certain set of beliefs (in harmony with what Billy Graham preached).

But for the outside world, it may be time for us to reconsider how we who are traditional evangelicals describe ourselves.

It might also lead to more conservatives to talk about Jesus and the Scriptures.

Shall we take that step?

Again, Brown failed to criticize evangelical leaders for hitching the movement to political and cultural issues.